Riddler Apples

May 8, 2020

Introduction

This was a challenging Riddler about a toddler's inefficient eating habits. Our picky toddler takes a bite from an Apple once every minute, and only if the randomly chosen spot has skin left on it. How long will it take to eat the entire apple? Spoiler - it's likely to outlast the toddler's attention span by quite some time. Here is the problem text with full details of this disastrously slow process.

A certain 2-year-old is eating his favorite snack: an apple. But he eats it in a very particular way. When he first receives the apple, and every minute thereafter, he rotates the apple to a random position and then looks down. If there’s any skin of the apple left in the spot where he plans to take a bite, then he will indeed take that bite. But if there’s no skin there (i.e., he’s already taken bites at that spot), he won’t take a bite and will rotate the apple for another minute. Once he has bitten off all the skin of the apple, he’s done eating.Suppose the apple is a sphere with a radius of 4 centimeters, and that each bite of the apple is a circle of the sphere whose radius, as measured along the apple’s curved surface, is 1 centimeter. On average, how many minutes will it take this 2-year-old to eat the apple?

Solution

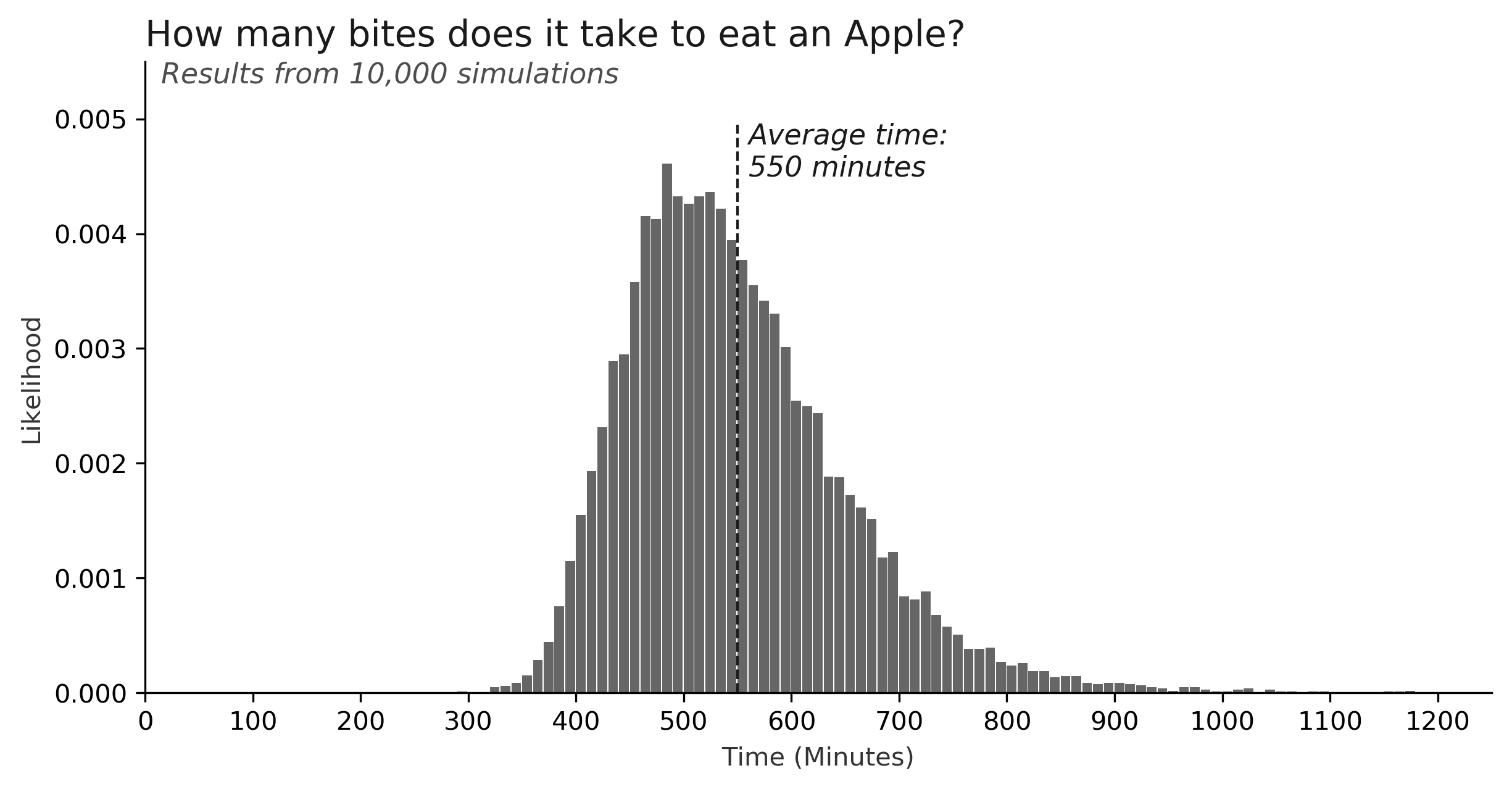

This week's answer is not perfectly precise, as I used a monte carlo simulation. Furthermore, because of the complexity of the problem, I was only able to run 10,000 scenarios, which means there is likely some variance in my answer compared to the "true" result. In any case, I can say with confidence that the toddler will be eating this apple for quite some time: on average, it will take roughly 550 minutes (more than 9 hours), to completely finish the snack.

Of course, because the process is random, each apple will be eaten differently. I've illustrated one scenario in the gif below. The apple is projected onto 2-dimensions (just like a map of the globe). Each red dot represents a point of skin on the apple's surface. At each step, the toddler chooses a random location, takes a bite, and the points in a nearby circle turn yellow. This gif shows just the first 150 bites, and it's not nearly enough to finish the apple. In fact this particular simulation doesn't finish until the 557th bite!

(I also found it fascinating to note how each bite is projected in two dimensions. Obviously each bite is a perfect circle on the 3-dimensional apple, but in this 2-dimensional projection, the bites can becomes distorted. Bites near the equator are nearly circular in shape, but bites near the poles become increasingly stretched out, owing to this particular method of projecting the globe into two dimensions. This is the exact same phenomena that makes Greenland look enormous on some maps of the world.)

In addition to this single scenario, we can also view the distribution of all 10,000 simulations. This chart shows a histogram of the number of bites it took for every apple to be eaten. The results range from roughly 200 minutes (3+ hours), to 1200 minutes (20 hours!)

Methodology

This was a challenging problem, and the only way I could think to tackle it was to simulate the process. In addition, rather than modeling the apple as a continuous, smooth sphere, I modeled a network of "sensors" scattered randomly and uniformly across its surface. I tracked whether each sensor still contained skin, and the simulation ended once all sensors had been "eaten". With a large enough number of sensors, e.g. 50,000, there should be little accuracy lost compared to a continuous model, and counting the sensors simplifies the problem significantly.

Before I dive into the details, I also found it helpful to list the steps needed to solve this problem. These are like "sub-problems" that each contribute to the overall solution. Each of these problems presented its own unique challenges.

- Choose a point randomly and uniformly on the apple's surface.

- Once a point is chosen, determine the area of the "bite".

- After each bite, track the total area of skin remaining.

Let's review how to solve each of these.

Choose a random point on the apple's surface

A pitfall to avoid here is that many algorithms for choosing uniform points in two dimensions will not be uniform in three dimensions. As an example, suppose you start by generating a random latitude (-90° to 90°) and longitude (-180° to 180°), then plotting that point on the sphere. After many iterations, you will find that your points are concentrated near the poles, and not uniformly distributed across the sphere's surface. This happens because each ring of latitude (which is chosen with the same probability) is a different size on the sphere: the rings near the equator are much larger, and points will be more spread out than the rings near the poles, which are smaller and more dense.

Fortunately, this problem is well known, and many algorithms exist to choose uniform points on the surface of a sphere. The next decision we have to make is what coordinate system we want to use. I chose cartesian coordinates, expressed as , in particular because it makes the next step easier.

In the python program I wrote, you can generate a random point on the surface of the apple easily. However, it's not quite as easy to imagine where those points are on the surface. I also included a method to be able to translate between cartesian and latitude/longitude systems.

# set a random seed for reproducibility

np.random.seed(42)

# create a new Apple object

apple = Apple()

# generate random points using cartesian coordinates (x, y, z)

points = apple.uniform_cartesian_samples(n_samples=2)

# array([[-3.41545755, -1.81930207, -1.01231898],

# [ 0.48038245, 3.28718639, 2.22792243]])

# convert to latitude/longitude (values in radians)

coords = apple.cartesian_to_lat_lon(points)

# array([[-2.65215412, -0.25586232],

# [ 1.42568564, 0.59074583]])

Determine the bite area

I chose to operate primarily in cartesian coordinates because it is easy to calculate "great circle distance". Great circle distance is the shortest distance between two points along the surface of the sphere. It's the path that an ant would take to walk from A to B. In this problem, a bite includes points up to 1cm away from the initial point. I wrote a method that returns all points within a certain radius, which will give us the points affected by a bite.

# set a random seed for reproducibility

np.random.seed(42)

# create a new Apple object

apple = Apple()

# select a random point to bite

bite_center = apple.random_sensor()

# array([-3.22979111, 2.21487782, -0.81410417])

# identify all the points within a 1cm radius

bite_points = apple.nearby_sensors(bite_center, radius=1.0)

# array([[-3.13397650e+00, 2.47674898e+00, -2.09537066e-01],

# [-2.96055610e+00, 2.67557705e+00, -2.76396469e-01],

# [-3.40621913e+00, 1.98721351e+00, -6.69816170e-01],

# ...

# [-2.81781602e+00, 2.32745616e+00, -1.62568777e+00],

# [-3.49884821e+00, 1.82905212e+00, -6.42362473e-01],

# [-2.86722633e+00, 2.76529043e+00, -3.63568444e-01]])

Track the total area of skin remaining

Now that we have a way to choose random points and calculate the size of a bite, we need a way to track the status of each sensor. One way to do this is to keep a set of sensors on the apple's surface that still have skin. Every time we take a bite, some sensors may be removed from this set if they are included in the bite. Once the set has zero elements (no more skin on the apple), then the simulation ends. In python, the eat method performs one simulation and returns the number of bites it took to eat the apple.

# set a random seed for reproducibility

np.random.seed(42)

# create an Apple object with 50,000 points tracked on its surface

apple = Apple(radius=4.0, n_sensors=50000)

# simulate one apple being eaten - returns the number of bites

results = apple.eat() # returns 577 - nearly 10 hours to eat!

Full Code

This week's solution is brute force and inefficient. It took several hours to generate 10,000 simulations. However, I think the logical flow of the program makes sense, and could be improved in the future. I created a Sphere class that has methods related to spheres, and an Apple class that inherits these methods in order to solve the problem. In particular there are methods for each of the steps above, like choosing random points, converting between coordinate systems, and simulating an apple being eaten.

"""Classes and functions to solve the Riddler Classic from May 8, 2020"""

import numpy as np

class Sphere:

"""

This class is used to model various properties of a sphere. For example, it

contains methods to calculate surface area, generate random, uniformly dist-

ributed points on the sphere's surface, calculate great circle distance bet-

ween points, and convert between coordinate systems such as cartesian, lati-

tude/longitude, etc.

Examples

--------

>>> sphere = Sphere(radius=4.0)

>>> sphere

<Sphere(radius=4.0)>

>>> np.random.seed(42)

>>> points = sphere.uniform_cartesian_samples(2)

>>> points

array([[ 2.40000818, -0.6680612 , 3.12948158],

[ 3.90868531, -0.60092837, -0.60088624]])

>>> sphere.cartesian_to_lat_lon(points)

array([[-0.27148532, 0.89846272],

[-0.1525474 , -0.15079237]])

"""

def __init__(self, radius: float) -> None:

self.radius = radius

def __repr__(self) -> str:

return f"<Sphere(radius={self.radius:,.1f})>"

def uniform_cartesian_samples(self, n_samples: int) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Returns an array of uniformly distributed points on the surface of this

sphere, expressed as cartesian coordinates, (x, y, z). The output array

will have shape (n_samples, 3).

"""

# we generate these points by sampling from a standard normal

# distribution for x, y, z, then normalizing each vector

points = np.random.normal(size=(n_samples, 3))

factor = (points ** 2).sum(1) ** 0.5

return self.radius * points / factor[:, None]

def great_circle_distance(

self, point: np.ndarray, points: np.ndarray

) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Returns the great circle distance between a single point and an array of

points. Points should be expressed in cartesian coordinates, (x, y, z).

"""

# ensure factor is between -1 and 1 before passing to arccos

factor = points @ point / self.radius ** 2

factor = np.clip(factor, a_min=-1.0, a_max=1.0)

return self.radius * np.arccos(factor)

def cartesian_to_lat_lon(self, points: np.ndarray) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Converts an array of cartesian points to an array of latitude/longitude.

The input array should have shape (n_samples, 3), and the output array

will have shape (n_sample, 2).

"""

latitude = np.arcsin(points[:, 2] / self.radius)

longitude = np.arctan2(points[:, 1], points[:, 0])

return np.vstack([longitude, latitude]).T

class Apple(Sphere):

"""

This class represents an Apple as a sphere with radius r. This class will be

used to solve the Riddler Classic from May 8, 2020, found here:

fivethirtyeight.com/features/can-you-eat-an-apple-like-a-toddler/

The basic approach is to model the Apple as a sphere with a fixed number of

discrete "sensor" points spread uniformly and randomly across its surface.

The sensors are used to track whether that particular point on the Apple

still contains skin. With enough sensors, we approach a continuous model of

the Apple's surface.

Ultimately, to answer the Riddler, call the `eat` method, which will run a

monte carlo simulation of taking bites until all skin has been eaten.

Examples

--------

>>> np.random.seed(42)

>>> apple = Apple(radius=4)

>>> apple

<Apple(radius=4.0, n_sensors=10,000)>

>>> apple.sensors[:5]

array([[ 2.40000818, -0.6680612 , 3.12948158],

[ 3.90868531, -0.60092837, -0.60088624],

[ 3.47558777, 1.68899767, -1.03323594],

[ 2.54700647, -2.17547878, -2.18633257],

[ 0.37406549, -2.95786657, -2.66666465]])

>>> apple.random_sensor()

array([-3.22979111, 2.21487782, -0.81410417])

>>> # run a single simulation of the bites it takes to finish the apple

>>> apple.eat()

425

"""

def __init__(self, radius: float = 4.0, n_sensors: int = 10000) -> None:

super().__init__(radius=radius)

self.n_sensors = n_sensors

self.sensors = self.uniform_cartesian_samples(n_samples=n_sensors)

def __repr__(self) -> str:

return (

f"<Apple("

f"radius={self.radius:,.1f}, "

f"n_sensors={self.n_sensors:,.0f})>"

)

def random_sensor(self) -> np.ndarray:

"""Returns a randomly selected sensor from the surface of the Apple"""

return self.sensors[np.random.choice(self.n_sensors)]

def nearby_sensors(

self, point: np.ndarray, radius: float = 1.0

) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Returns all sensors within a given radius of a point, measured along the

surface of the Apple (i.e. the great circle distance).

"""

distance = self.great_circle_distance(point, self.sensors)

return self.sensors[distance < radius]

def eat(self, bite_radius: float = 1.0) -> int:

"""

Solves the Riddler by simulating eating this Apple. Start with a fresh

Apple, where every "sensor" on the Apple's surface contains skin. Then

we simulate taking a bite with a given radius, measured on the Apple's

surface. Each sensor within the bite radius is removed from the set of

sensors containing skin. Continue this process until no skin remains.

"""

n = 0

skin = set(tuple(sensor) for sensor in self.sensors)

while skin: # keep going if at least one sensor has skin remaining

location = self.random_sensor()

eaten = self.nearby_sensors(point=location, radius=bite_radius)

skin -= set(tuple(sensor) for sensor in eaten)

n += 1

return n

def write_results(self, output_file: str) -> None:

"""Run simulations and write to a file until KeyboardInterrupt"""

with open(output_file, "w") as output:

try:

while True:

trial = self.eat()

output.write(f"{trial}\n")

print(trial)

except KeyboardInterrupt:

pass

if __name__ == "__main__":

import doctest

doctest.testmod()

# these simulations are quite slow: about 2 per second. As a result, I'll

# write the results to a file and run them in the background for a while.

apple = Apple(radius=4.0, n_sensors=25000)

apple.write_results("20200508-riddler-results.txt")