Riddler Birthdays

Oct 4, 2019

Introduction

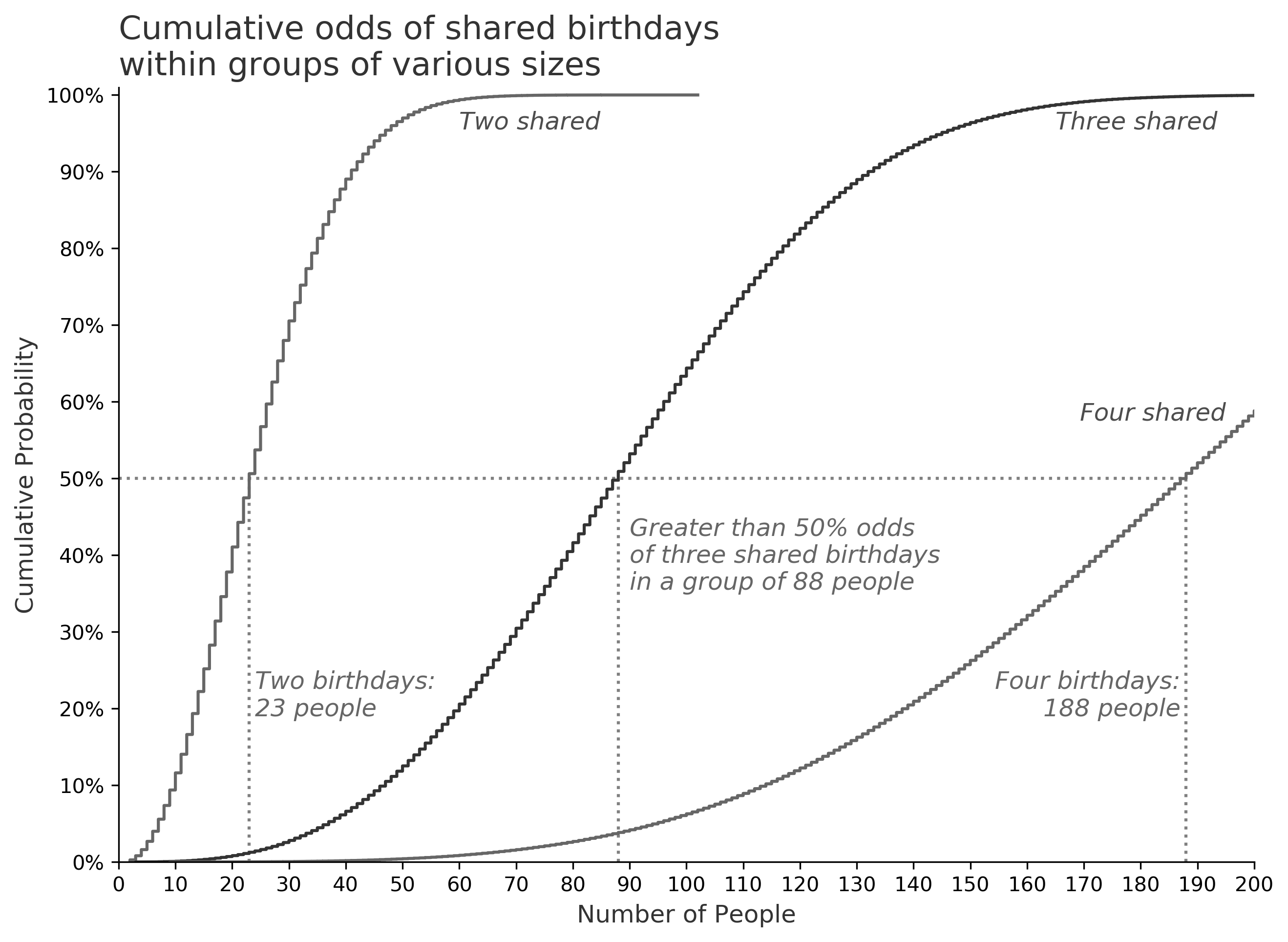

This week's Riddler is a twist on the classic birthday problem. The birthday problem tells us that among a group of just 23 people, we are 50% likely to find at least one pair of matching birthdays. But what if we want to find three matching birthdays instead?

In the U.S. Senate, three senators happen to share the same birthday of October 20: Kamala Harris, Brian Schatz and Sheldon Whitehouse.How many people do you need to have better-than-even odds that at least three of them have the same birthday? (Again, ignore leap years.)

Solution

The US Senate comprises a group of 100 individuals. It turns out that for a group of that size, we expect three shared birthdays roughly 64% of the time. For 50% odds, we need a group of 88 people.

Methodology

The classic birthday problem can be solved with pen, paper, and probability. We consider two possibilities: no shared birthdays, or at least one shared birthday. Because these are the only two possibilities, their odds must sum to 100%. It's often easier to solve for the likelihood of all unique birthdays, then subtract that answer from 100% to solve the problem.

However, with three birthdays the math becomes much more involved. For a group of size , we would have to partition the world into categories like this:

- distinct birthdays

- 1 pair of birthdays & distinct birthdays

- 2 pairs of birthdays & distinct birthdays

- 3 pairs of birthdays & distinct birthdays ...

At the extreme, we would have pairs of birthdays (everyone in the group has a birthday buddy). The final option would be that at least three people share the same birthday. We sum the likelihoods of everything except the probability we're interested in, subtract from 100%, and arrive at our answer.

Instead, I opted to solve this problem using simulated trials. By simulating enough groups and measuring how many people are needed to find three matching birthdays, we can estimate the answer. If we simulate one million groups, we can measure the median group size of our samples to find the point at which we cross 50% likelihood.

Python does the heavy lifting this week. The function itself is short, but we rely on a million sampled groups to converge on the correct answer.

import random

def model(n=3, days=365):

size = 0

seen = [set() for _ in range(n)]

while len(seen[-1]) == 0:

i = random.randint(a=0, b=days)

for s in seen:

if i not in s:

s.add(i)

break

size += 1

return size

Each time we run model(), it returns a random sample of the number of people required to find three matching birthdays. The function is also general enough to search for any number of desired birthdays - for example, the number of people we need for four matching birthdays - though the speed decreases as we search for larger numbers.

The function tracks the number of occurrences of each birthday in the group. In the default case, looking for three matching birthdays, it tracks the number of birthdays we've seen only once, and the number of birthdays we've seen twice. For each new random number we draw, we determine how many times we've seen it before. If it's brand new, we add it to the first set. If we've seen it once before, we add it to the second set. And if we've seen it twice before, we know we've found the third instance, so the function halts and returns the number of birthdays we needed to see in total.

The chart below shows the cumulative curves for two, three, and four matching birthdays. As we know from the classic problem, we reach 50% cumulative likelihood with a group of 23. For three birthdays, we need 88, and for four birthdays we need 188! Therefore the House of Representatives is more likely than not to have at least four matching birthdays.