Riddler Countdown

May 31, 2019

Introduction

Computers continue to fascinate me. The Riddler this week deals with an explosion of combinations and math that is nearly impossible to grasp without the help of a computer. Specifically, we're interested in crafting an ideal strategy for the "numbers game" from the UK television show Countdown. The numbers game asks contestants to use four mathematical operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division) with six numbers as inputs to solve for a single, three digit target. Most of the time, this can be quite difficult, especially with a 30-second time limit. However, with the help of a computer, we can solve for every possible combination of input and output to identify the strategy that gives the humans the best chance to win!

Here is the complete problem text.

My favorite game show is “Countdown” on Channel 4 in the UK. I particularly enjoy its Numbers Game. Here is the premise: There are 20 “small” cards, two of each numbered 1 through 10. There are also four “large” cards numbered 25, 50, 75 and 100. The player asks for six cards in total: zero, one, two, three or four “large” numbers, and the rest in “small” numbers. The hostess selects that chosen number of “large” and “small” at random from the deck. A random-number generator then selects a three-digit number, and the players have 30 seconds to use addition, subtraction, multiplication and division to combine the six numbers on their cards into a total as close to the selected three-digit number as they can.There are four basic rules: You can only use a number as many times as it comes up in the six-number set. You can only use the mathematical operations given. At no point in your calculations can you end on something that isn’t a counting number. And you don’t have to use all of the numbers.

For example, say you ask for one large and five smalls, and you get 2, 3, 7, 8, 9 and 75. Your target is 657. One way to solve this would be to say 7×8×9 = 504, 75×2 = 150, 504+150 = 654 and 654+3 = 657. You could also say 75+7 = 82, 82×8 = 656, 3-2 = 1 and 656+1 = 657.

This riddle is twofold. One: What number of “large” cards is most likely to produce a solvable game and what number of “large” cards is least likely to be solvable? Two: What three-digit numbers are most or least likely to be solvable?

Thanks to Laurent Lessard who pointed out a bug in an earlier version of my code. It's since been updated.

Solution

This Riddler was quite complicated, but it was also one of my favorites because it combined healthy doses of math, probability, combinatorics, and computer programming. I'll start by showing the results, then continue by walking through my solution for readers interested in the details. (Or you can skip to the full code at the bottom of the article!)

The first part of the question asked us to identify the number of 'large' cards that would be expected to produce the most or least solvable puzzles. Recall that we start the game by selecting either 0, 1, 2, 3, or all 4 large numbers, so let's examine our odds of solving the puzzle given those starting conditions. The table below shows our inputs: the number of large and small numbers, the total number of combinations we could receive, the total number of solvable puzzles that could be created from those inputs, and the percent of solvable puzzles, which is the column we're interested in.

We should select two large numbers and four small numbers in order to have the best odds of creating a solvable puzzle. If we do so, we create a solvable puzzle roughly 98% of the time. On the other hand, if we wanted to make things difficult for ourselves, we could choose zero large numbers, leaving us with roughly 84% odds of any valid solution existing.

| Large # | Small # | Combinations Large | Combinations Small | Combinations Total | Sum of Solvable Targets | % of Solvable Targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6 | 1 | 38,760 | 38,760 | 29,261,974 | 83.88% |

| 1 | 5 | 4 | 15,504 | 62,016 | 54,558,826 | 97.75% |

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 4845 | 29,070 | 25,690,882 | 98.20% |

| 3 | 3 | 4 | 1140 | 4560 | 3,887,884 | 94.73% |

| 4 | 2 | 1 | 190 | 190 | 154,693 | 90.46% |

| 134,596 | 113,554,259 | 93.74% |

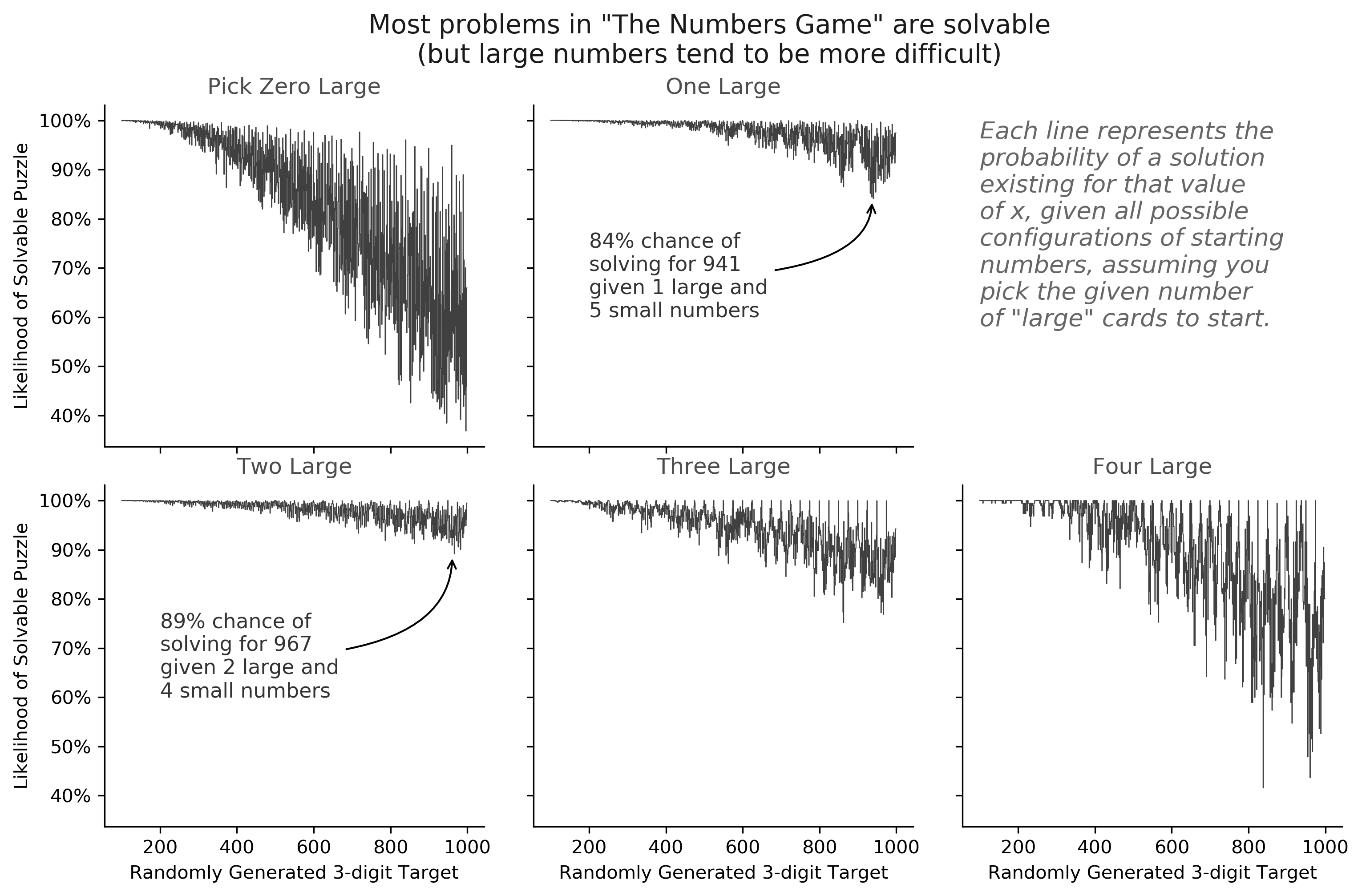

The second part of the question asked us to identify which three-digit numbers would be more or less likely to be valid solutions. Obviously this depends on our choice of large numbers, so I'll show the likelihood of each number being a valid solution given each of the five initial conditions. In fact, the chart below helps us visualize several key trends.

- We confirm that choosing two large cards gives us the highest average probability of finding a solution. The chart on the bottom left has higher values across all target numbers than any other chart.

- Higher target numbers are harder to solve for. In fact, several values, like 967 and 863 are more difficult to solve, regardless of the number of large cards we choose.

- "Round" numbers, like 200, 250, 300, etc. are much easier to solve consistently when we choose more large cards. This makes sense, given that we're more likely to find the 50 or 100 card when we select more from that pool, but isn't enough of an incentive to sacrifice the valuable "small" numbers that help us fill in the gaps.

Here is a table of the most difficult numbers to solve, given a starting number of large cards. For example, if we choose 1 large card and 5 small cards, and our target number is 941, then across all the different combinations of numbers we could be given, we will be able to solve the puzzle just 84% of the time.

| Pick 0 Large | Pick 1 Large | Pick 2 Large | Pick 3 Large | Pick 4 Large |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 997, 36.9% | 941, 84.1% | 967, 89.2% | 863, 75.2% | 839, 41.6% |

| 947, 38.5% | 937, 84.4% | 983, 90.1% | 967, 76.9% | 961, 43.7% |

| 983, 39.2% | 933, 85.2% | 977, 90.6% | 961, 77.2% | 955, 47.9% |

| 941, 40.4% | 947, 85.4% | 961, 90.9% | 862, 77.3% | 967, 48.9% |

| 929, 41.3% | 863, 86.5% | 863, 91.3% | 964, 79.4% | 965, 51.6% |

And here is the list of easiest values to solve. If we choose at least 1 large card, there are some target values that can be solved with every possible configuration of starting numbers! For example, numbers like 100, 150, 200, and other round numbers become completely solvable once we have enough "large" numbers to work with.

| Pick 0 Large | Pick 1 Large | Pick 2 Large | Pick 3 Large | Pick 4 Large |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 108, 99.997% | 25 @ 100% | 36 @ 100% | 57 @ 100% | 203 @ 100% |

| 120, 99.99% | ||||

| 105, 99.98% | ||||

| 104, 99.98% | ||||

| 112, 99.98% |

Methodology

Even though we ultimately want to solve this problem for a pool of six numbers, let's start by considering just two. We want to build a function that takes two numbers as inputs and returns all valid numbers they can produce using addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. We also want the function to return each of the numbers themselves, because we aren't required to use all the numbers available to us.

Here's an example using the numbers and . Our function should return:

We also need a way to store each of these values. For this problem, I used one of python's default data structures: sets. Sets are similar to arrays, except they are unordered collections of unique elements, such as {1,3,5,7}. If we attempt to add another 5 to this set, it will remain unchanged. This becomes very useful for our purposes here. For example, we can reproduce the logic above using this python function. (Note, I called the function two because it takes two numbers as inputs; later we'll have functions for three, four, five, and six. The naming conventions leave something to be desired, and probably deserve to be refactored later...)

The function is relatively straightforward. We always include a, b, addition, subtraction, and multiplication. We only include or if it is a whole number.

def two(a, b):

"""

Returns a set of all valid combinations of a and b:

identity of a, identity of b, addition, subtraction,

multiplication, and division

"""

out = {a, b, a+b, a-b, b-a, a*b}

try:

if a/b == int(a/b): out.add(int(a/b))

except ZeroDivisionError:

pass

try:

if b/a == int(b/a): out.add(int(b/a))

except ZeroDivisionError:

pass

return out

# examples

>>> two(4, 5)

{-1, 1, 4, 5, 9, 20}

>>> two(2, 4)

{-2, 2, 4, 6, 8}

Now we have created the universe of valid targets for any two numbers. How could we handle three numbers, such as , , and ? We could add and , then multiply by , or subtract from then divide by , we might want to ignore completely, or consider many other possibilities. Fortunately, we can use recursion to delegate this explosion of possibilities to the computer.

First, we create the list of valid numbers that we can derive from and . Then, for each possible output, we combine it with . For example, we found above that and combine to give us a set of . If our third value were , then we would also want to find all numbers we could create from pairs of .

However, we could also start by pairing and , then pairing those outputs with . The answers we get depend on the order of operations! For this, we want to combine and first, giving us a set of . Then we would pair each of those values with . Finally, we would generate all values from and and pair each of them with our last number, . All told, we need to perform three "combinations of combinations".

Each time we generate new possible derived values, we want to add them to a master set of all values we were able to create. Sets in python have the mathematical operations we expect, such as the "union". When we take the union of two or more subsets, we return every number that occurs in at least one of the subsets. The final union of our three combinations tells us every possible number we can create starting from the original three.

Here is how I implemented this in python. The * notation is python's list unpacking, which helps us collect each unique value we generate through the mathematical operations and store them in a single, larger set. We see that every possible number we can generate starting with , , and is 30 numbers ranging from to . You can verify this, though it takes some time, using pen and paper!

def three(a, b, c):

return set().union(*[

*[two(x, a) for x in two(b, c)],

*[two(x, b) for x in two(c, a)],

*[two(x, c) for x in two(a, b)],

])

# examples

>>> three(3, 4, 5)

{-17, -11, -8, -7, -6, -5, -4, -3, -2, -1,

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 15,

17, 19, 20, 23, 27, 32, 35, 60}

Now we've established a method to find solutions for larger and larger pools of numbers. Each time we increase the numbers available to us, we call the prior function several times on each new combination of numbers, then take the union of all the sets we create. Eventually, we create a function that takes six numbers as arguments and returns a set of all valid combinations of those numbers. These sets can get quite large. For example, we can create 3,918 values using the numbers , , , , , and .

Ultimately, we want to filter those sets for the target range we care about, which is three-digit numbers. This time, we use another operation on sets: the intersection. We're only interested in the combinations of our six numbers that fall between 100 and 999. In python, I wrote the countdown function to do this, shown below. It returns a set of up to 900 numbers (the most available in our desired range), for any six numbers.

def countdown(a, b, c, d, e, f, low=100, high=999):

"""

Returns the valid mathematical combinations of the six inputs

that fall between a range of "low" and "high"

"""

return six(a, b, c, d, e, f).intersection(range(low, high+1))

However, we're not done yet. We've built a general purpose solution-checker for any six numbers, but we need to consider which six numbers we're likely to receive on the show. To do this, we create two lists of all possible cards, separated into large and small numbers. Then we use these lists to generate all possible number pools, given our choice of large cards to start with.

# four large numbers: 25, 50, 75, and 100, and 20 small numbers from 1-10

LARGE = [25, 50, 75, 100]

SMALL = 2*[*range(1, 11)]

def number_pool(n_large, total=6):

"""

Returns a list of randomly selected numbers where the

returned list has "n_large" numbers selected from the

LARGE list, and "total - n_large" numbers selected

from the SMALL list.

"""

# ensure we don't try to pick more numbers than available

n_large = min(len(LARGE), n_large)

# generate the list of numbers, then sort it before returning

out = (

list(L) + list(S)

for L in combinations(LARGE, n_large)

for S in combinations(SMALL, total - n_large)

)

return [sorted(x) for x in out]

For example, the number pool with n_large=1 is a list of all 62,016 different six-number pools we could possibly see on the show, such as , or . Each of those 62,016 number pools has its own solution space: the numbers we could create between 100 and 999 using them. We can create all 900 unique target numbers using , and just 736 from . If it were just those two possibilities, we would say our average probability of success is . Using our code, we can calculate the probability of solving for all target values starting with all number pools.

def solvable_percent(n_large, total=6, low=100, high=999):

"""

Returns the percent of random targets that can be solved

given a list of six numbers comprised of "n_large" LARGE

numbers and "total - n_large" SMALL numbers.

"""

# create number list given a number of LARGE numbers

numbers = number_pool(n_large=n_large, total=total)

# run each group of numbers to count the total number of solvable targets

numerator = sum([solvable_count(*n, low=low, high=high) for n in numbers])

denominator = len(numbers) * len(mask)

return numerator / denominator

>>> solvable_percent(n_large=2)

0.9819547452509269

And this function, built slowly from its humble roots of comparing two numbers, allows us to solve the problem! We simply call this function with a given number of large cards, and it returns the likelihood that we would see a solvable puzzle from all possible number pools and random targets. Importantly, this is an exact solution - no simulation required!

The second part of the question asked us to identify the target values that were most likely to be solvable. Up to this point, we didn't particularly care "how solvable" a target value was; we only cared that there was a way to solve it. But using our functions from above, we can tally the number of target values that are most and least likely to occur given our starting number pools, and our work here is done. The full code is available below.

Full Code

This was an extremely fun problem to work on, and finding a way to explore the hundreds of millions of combinations simply and quickly was a challenge. There are certainly further optimizations to explore, such as simplifying the code for the four, five and six functions, now that I know how everything should work. But the process of building this was extremely enjoyable. Let me know if you find ways to improve this!

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Solves the Riddler Classic from May 31, 2019

In the 'numbers game' from the television show 'Countdown',

what number of large numbers (from zero to four) gives the

highest likelihood of being able to match a random number

between 100 and 999?

"""

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from functools import lru_cache

from itertools import combinations

# four large numbers: 25, 50, 75, and 100, and 20 small numbers from 1-10

LARGE = [25, 50, 75, 100]

SMALL = 2*[*range(1, 11)]

@lru_cache(maxsize=None)

def two(a, b):

"""

Returns a set of all valid combinations of a and b:

identity of a, identity of b, addition, subtraction,

multiplication, and division

"""

out = {a, b, a+b, a-b, b-a, a*b}

try:

if a/b == int(a/b): out.add(int(a/b))

except ZeroDivisionError:

pass

try:

if b/a == int(b/a): out.add(int(b/a))

except ZeroDivisionError:

pass

return out

@lru_cache(maxsize=None)

def three(a, b, c):

return set().union(*[

*[two(x, a) for x in two(b, c)],

*[two(x, b) for x in two(c, a)],

*[two(x, c) for x in two(a, b)],

])

@lru_cache(maxsize=None)

def four(a, b, c, d):

return set().union(*[

*[two(x, a) for x in three(b, c, d)],

*[two(x, b) for x in three(c, d, a)],

*[two(x, c) for x in three(d, a, b)],

*[two(x, d) for x in three(a, b, c)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(a, b) for y in two(c, d)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(a, c) for y in two(b, d)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(a, d) for y in two(b, c)],

])

@lru_cache(maxsize=None)

def five(a, b, c, d, e):

return set().union(*[

*[two(x, a) for x in four(b, c, d, e)],

*[two(x, b) for x in four(c, d, e, a)],

*[two(x, c) for x in four(d, e, a, b)],

*[two(x, d) for x in four(e, a, b, c)],

*[two(x, e) for x in four(a, b, c, d)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(a, b) for y in three(c, d, e)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(a, c) for y in three(b, d, e)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(a, d) for y in three(b, c, e)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(a, e) for y in three(b, c, d)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(b, c) for y in three(a, d, e)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(b, d) for y in three(a, c, e)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(b, e) for y in three(a, c, d)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(c, d) for y in three(a, b, e)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(c, e) for y in three(a, b, d)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(d, e) for y in three(a, b, c)],

])

@lru_cache(maxsize=None)

def six(a, b, c, d, e, f):

return set().union(*[

*[two(x, a) for x in five(b, c, d, e, f)],

*[two(x, b) for x in five(c, d, e, f, a)],

*[two(x, c) for x in five(d, e, f, a, b)],

*[two(x, d) for x in five(e, f, a, b, c)],

*[two(x, e) for x in five(f, a, b, c, d)],

*[two(x, f) for x in five(a, b, c, d, e)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(a, b) for y in four(c, d, e, f)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(a, c) for y in four(b, d, e, f)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(a, d) for y in four(b, c, e, f)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(a, e) for y in four(b, c, d, f)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(a, f) for y in four(b, c, d, e)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(b, c) for y in four(a, d, e, f)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(b, d) for y in four(a, c, e, f)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(b, e) for y in four(a, c, d, f)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(b, f) for y in four(a, c, d, e)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(c, d) for y in four(a, b, e, f)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(c, e) for y in four(a, b, d, f)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(c, f) for y in four(a, b, d, e)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(d, e) for y in four(a, b, c, f)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(d, f) for y in four(a, b, c, e)],

*[two(x, y) for x in two(e, f) for y in four(a, b, c, d)],

*[two(x, y) for x in three(a, b, c) for y in three(d, e, f)],

*[two(x, y) for x in three(a, b, d) for y in three(c, e, f)],

*[two(x, y) for x in three(a, b, e) for y in three(c, d, f)],

*[two(x, y) for x in three(a, b, f) for y in three(c, d, e)],

*[two(x, y) for x in three(a, c, d) for y in three(b, e, f)],

*[two(x, y) for x in three(a, c, e) for y in three(b, d, f)],

*[two(x, y) for x in three(a, c, f) for y in three(b, d, e)],

*[two(x, y) for x in three(a, d, e) for y in three(b, c, f)],

*[two(x, y) for x in three(a, d, f) for y in three(b, c, e)],

*[two(x, y) for x in three(a, e, f) for y in three(b, c, d)],

])

@lru_cache(maxsize=None)

def countdown(a, b, c, d, e, f, low=100, high=999):

"""

Returns the valid mathematical combinations of the six inputs

that fall between a range of "low" and "high"

"""

return six(a, b, c, d, e, f).intersection(range(low, high+1))

@lru_cache(maxsize=None)

def solvable_count(a, b, c, d, e, f, low=100, high=999):

"""

Returns the number of solvable targets from the mask range

"""

return len(countdown(a, b, c, d, e, f, low=low, high=high))

@lru_cache()

def number_pool(n_large, total=6):

"""

Returns a list of randomly selected numbers where the

returned list has "n_large" numbers selected from the

LARGE list, and "total - n_large" numbers selected

from the SMALL list.

"""

# ensure we don't try to pick more numbers than available

n_large = min(len(LARGE), n_large)

# generate the list of numbers, then sort it before returning

out = (

list(L) + list(S)

for L in combinations(LARGE, n_large)

for S in combinations(SMALL, total - n_large)

)

return [sorted(x) for x in out]

def solvable_percent(n_large, total=6, low=100, high=999):

"""

Returns the percent of random targets that can be solved

given a list of six numbers comprised of "n_large" LARGE

numbers and "total - n_large" SMALL numbers.

"""

# create number list given a number of LARGE numbers

numbers = number_pool(n_large=n_large, total=total)

# run each group of numbers to count the total number of solvable targets

numerator = sum([solvable_count(*n, low=low, high=high) for n in numbers])

denominator = len(numbers) * len(mask)

return numerator / denominator

@lru_cache()

def target_percent(n_large, total=6, low=100, high=999):

"""

Returns a pandas Series indexed by targets, with values

equal to the likelihood of being able to successfully hit

the target given a random set of input numbers.

"""

numbers = number_pool(n_large=n_large, total=total)

targets = [countdown(*n) for n in numbers]

targets = [elem for subset in targets for elem in subset]

targets = np.histogram(targets, bins=range(low, high+2))

targets = pd.Series(index=targets[1][:-1], data=targets[0])

return targets.div(len(numbers))

def plot_target_percent(n_large, total=6, low=100, high=999):

"""

Returns a bar graph of the target numbers and their likelihood

of being solvable, given a number of LARGE numbers in the pool.

"""

targets = target_percent(n_large=n_large, total=total, low=low, high=high)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10,7))

targets.plot(drawstyle='steps')

ax.set_xticks(range(low, high+2, 50))

ax.set_xlim(low, high+1)

for s in ['top', 'right']:

ax.spines[s].set_visible(False)

return ax