Riddler Thrones

May 17, 2019

Introduction

This week's Riddler pits the army of the dead vs. the army of the living. As the two armies battle, any fallen soldiers from the living army rise to fight with the dead. How many soldiers would each side need to make it a fair fight? Here's the full problem text:

At a pivotal moment in an epic battle between the living and the dead, the Night King, head of the army of the dead, raises all the fallen (formerly) living soldiers to join his ranks. This ability obviously presents a huge military advantage, but how big an advantage exactly?Forget the Battle of Winterfell and model our battle as follows. Each army lines up single file, facing the other army. One soldier steps forward from each line and the pair duels — half the time the living soldier wins, half the time the dead soldier wins. If the living soldier wins, he goes to the back of his army’s line, and the dead soldier is out (the living army uses dragonglass weapons, so the dead soldier is dead forever this time). If the dead soldier wins, he goes to the back of their army’s line, but this time the (formerly) living soldier joins him there. (Reanimation is instantaneous for this Night King.) The battle continues until one army is entirely eliminated.

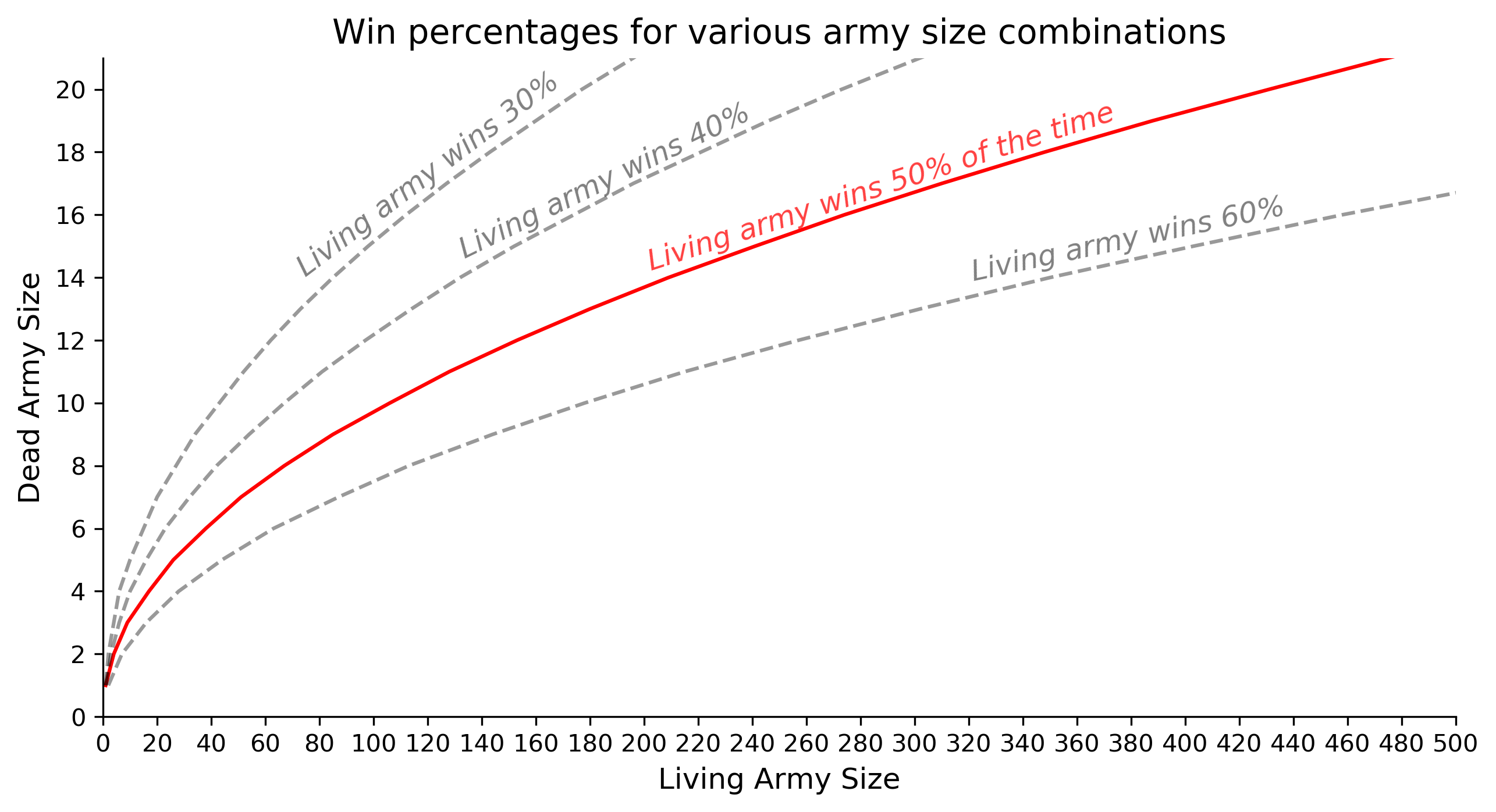

What starting sizes of the armies, living and dead, give each army a 50-50 chance of winning?

Setup

As with most Riddlers, I'll use Python to do much of the computation. However, it is still up to us to translate the problem into something our computers can understand.

First, let's deal with the inputs. We want the first input, , to be the number of soldiers in the living army. The next input, , will be the number of soldiers in the dead army. We also need a function that takes both and as inputs and returns a probability, which I'll define as the likelihood that the living army prevails in the battle. This will be a number between 0 and 1. For example, if the living army has 100 soldiers and the dead army has 50 soldiers, what is the likelihood the living army will win the battle?

Then, to solve the problem as stated above, we'll need another function that accepts either or , but not both, and returns the other variable such that the odds of winning are 50% for both sides. For example, we might want to know how many soldiers the living army needs to have fair odds against a dead army with 50 soldiers. Or we might want to know how many soldiers the dead army would need to battle against a living army of 500.

We know that soldiers in the army fight one at a time until one of the armies is depleted. Therefore, we know the terminating case of our program could be either or . We also define a "reward" in each terminating state, which will help us calculate the probabilities of each army winning. Define the reward when as 1. This means that if the living army wins the battle with any number of soldiers remaining, then the reward is 1. On the other hand, if the dead army wins the battle, we terminate with , and we set the reward to 0.

Lastly, we know how to move from different values of and to other values. For example, we know that if both armies start with 10 soldiers each, one of two things could happen.

- The living soldier wins. Then the living army remains at 10 soldiers, and the dead army goes from 10 soldiers to 9.

- The dead soldier wins. Then the living army goes from 10 to 9 soldiers, and the dead army goes from 10 to 11 soldiers. This is the advantage of night king!

Therefore, we move from a state of (, ) to a state of (, ) with 50% probability and to a state of (, ) with the other 50% probability. This is everything we need to write a recursive function that fully describes the battle!

The Code

The function below calculates the likelihood that the living army wins the battle, given a starting number of soldiers for each side. Importantly, the function is memoized, which means that answers it's already calculated are saved and stored so we don't repeat any steps we've already done.

What is interesting to me is that the problem clearly has elements of randomness: each duel has 50% likelihood of ending in either army's favor. But the function below doesn't need to simulate that randomness. Instead, it uses expected values and calculates exact probabilities.

from functools import lru_cache

@lru_cache(maxsize=None)

def model(living, dead, win_rate=0.5):

"""

Calculate the likelihood of the living army winning the battle,

given a starting army size for both living and dead.

Parameters

----------

living : int, the starting number of living soldiers

dead : int, the starting number of dead soldiers

win_rate : float, between 0 and 1, the likelihood of a living

soldier winning a single duel

Returns

-------

outcome : float, between 0 and 1, the likelihood of the living

army winning the entire battle

"""

if dead < 1:

# living army wins

return 1.0

elif living < 1:

# dead army wins

return 0.0

else:

# return the weighted average of both potential branches

return (

win_rate * model(living, dead - 1, win_rate)

+ (1 - win_rate) * model(living - 1, dead + 1, win_rate)

)

>>> model(1, 1)

0.5

>>> model(10, 5)

0.30745625495910645

Everything we described above shows up in this code. If we enter into a terminating condition with either or , we end the calculation and return the 1 or 0. Otherwise, we branch into the two possible worlds where the living soldier and the dead soldier each win their battle. The end result of this recursion is a final probability that takes all of the branching possibilities into account.

We can also validate our results by looking at the base case of . In this simple case, our final answer should be exactly equal to the soldiers' individual probability of winning a duel, because only one duel will occur before the battle is over. This makes sense, because we know the winner of the single duel determines the overall winner of the battle, and each duel is won by the living soldier 50% of the time. This is confirmed when we see that model(1, 1) returns 50%.

We now have a function that solves for the probability of the living army winning a battle with any combination of starting army sizes. However, that's not quite enough to solve the problem on its own. We know how to find probability based on army sizes, but we also need to be able to find army sizes from a probability. We'll tackle that next.

Graphing the Results

As usual, graphing the results can help to understand the dynamics of this problem. We know the dead army has a significant advantage, but exactly how much? We can use the function from the prior section to map all combinations of army sizes to try to understand the probability surface.

As we can see, the dead army's advantage compounds as it grows. In other words, each additional dead army soldier requires an increasing number of additional living army soldiers to fight. When the dead army has 10 soldiers, it requires 106 living soldiers just to keep the odds fair and square. I've also plotted the soldiers required for different battle probabilities. For example, if the living army wants to win with 60% certainty instead of 50%, it needs even more soldiers.

The relationship here is very close to a square root. For example, if we want to solve for the number of dead soldiers required for 50% odds, given a fixed number of living soldiers, we should take the square root. For example, if the dead army fights a living army with 400 soldiers, it should send roughly 20 of its own for a fair fight. Conversely, if the living army knows how many soldiers it will be facing, it should plan to amass that number squared! Even though the purpose of this Riddler was to solve for even odds, it's hard to imagine how the odds are not stacked in the night king's favor.